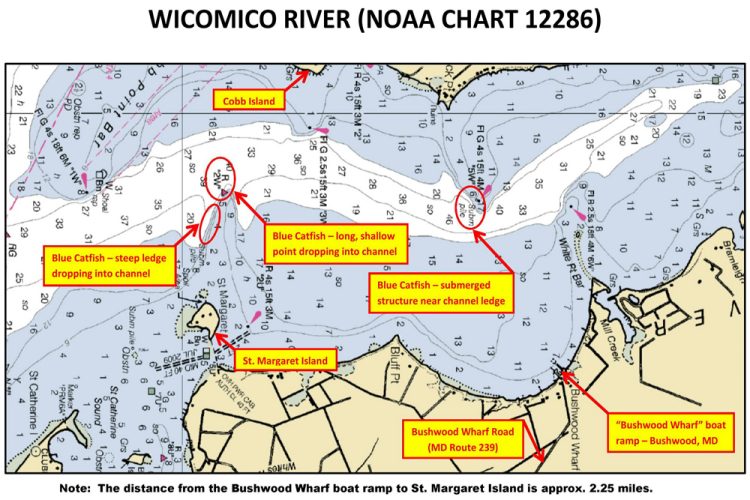

On this nautical chart, the author has identified several drop-offs from which he has consistently caught blue catfish within a stretch of Maryland’s Wicomico River. NOAA charts like this feature a lot of information about structure that is useful for pinpointing actively biting catfish. (Brad Hierstetter photo)

Finding Active Catfish Without Electronics

By Brad Hierstetter

Reliable ways to locate structure and cover that attract active catfish.

In this article, I will discuss several surefire ways that don’t rely on a fish finder to efficiently locate the structure and cover that attract active catfish year-round. Recall that structure is simply any change (drastic or subtle) in bottom contour: channels, ledges (aka drop-offs), flats, points and the like. Cover is anything that can hide a catfish or baitfish. Objects such as stumps, rocks and wrecks are examples of cover.

If you are fortunate enough to catfish in coastal waterways or in the Great Lakes, nautical charts produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are an ideal starting point. These charts contain highly detailed information on water depths, navigational obstructions (rocks and shipwrecks) and navigational aids (buoys and beacons). Intended to display for boaters the “hidden dangers to navigation,” these charts are invaluable resources for any catfish angler who seeks to quickly and accurately identify specific locations to fish for active catfish.

Armed with a small amount of basic interpretational knowledge, anglers in search of active catfish can easily leverage the fish-finding potential of these nautical charts. For example, two or more contour lines running closely together indicate a ledge; the more lines near one another, the steeper the ledge. An icon resembling a football with its laces facing up marks a sunken wreck.

Furthermore, here are a few abbreviations used which anglers may find useful: “hrd” (hard), “so” (soft), “Le” (ledge), “Obstn” (obstruction), “Rk” and “Rky” (rocks and rocky), “Ru” (ruin), “Subm piles” (submerged piles) and “Wk” (wreck). Be sure to refer to “U.S. Chart No. 1” for a description of the symbols, abbreviations and terms used on NOAA’s nautical charts. The most current edition of U.S. Chart No. 1 can be found online, here: http://www.nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/mcd/chartno1.htm

NOAA has started to cancel its production and maintenance of traditional paper nautical charts, with full cancellation scheduled by January 2025. Users are instead encouraged to utilize NOAA’s Electronic Navigation Chart, or ENC, which can be located online, here: https://charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml#mapTabs-1

Aside from using a fish finder, how else can catfish anglers locate structure and cover that attract active catfish? One of the easier methods is to locate buoys. Government agencies place buoys in the water to provide boaters with indicators, such as the presence of a natural or manmade object, a meaningful change in water depth, a channel, etc. It is common for active catfish to frequent all these areas. Earlier this summer, I was unable to use my fish finder because I failed to charge the battery. Despite this setback, my son and I had a productive catfish outing simply by anchoring, then fishing near and between the red and green channel-marking buoys within a small and generally very shallow creek.

Awareness of the inherent geographical characteristics of rivers and creeks can also be useful. For example, outside river bends are nearly always deeper than inside bends. Additionally, another constant is that rivers are comprised of a series of riffles, holes (sometimes called pools) and runs. If you wish to fish in deeper water, find a hole, which will always be between a riffle and a run.

Remember, too, that some land-based features often “carry into” the water. For example, riprap, which is a layer of large stones that humans place along shorelines to protect them against erosion, often extends several feet into the water. It is also common for a drop-off in the water to coincide with the presence of a hill on the adjacent shoreline.

The topics discussed here, as well as in the other articles I have written for CatfishNow this year, comprise some of the basics all catfish anglers should strive to master. Always remember that small adjustments (in this case, how you determine where to fish), when factored collectively, typically go a long way to tilting the odds in favor of the catfish angler.

(In 2012 and 2013, Brad Hierstetter and his long-time friend, Mike Dodge, won two Potomac River Monster Cat tournaments on the tidal Potomac River. Hierstetter enjoys sharing the basics that can help any angler catch more catfish, more often.)