Those of you learning the basics of catfishing would do well to look back at the tactics shared by the anglers of yesteryear. As we embrace modern techniques and technology, it’s wise not to overlook the wealth of timeless knowledge left by those who came before us. Our ancestors’ profound wisdom, creativity and innovation form a treasure trove of great knowledge that can help us be more successful catfish anglers today.

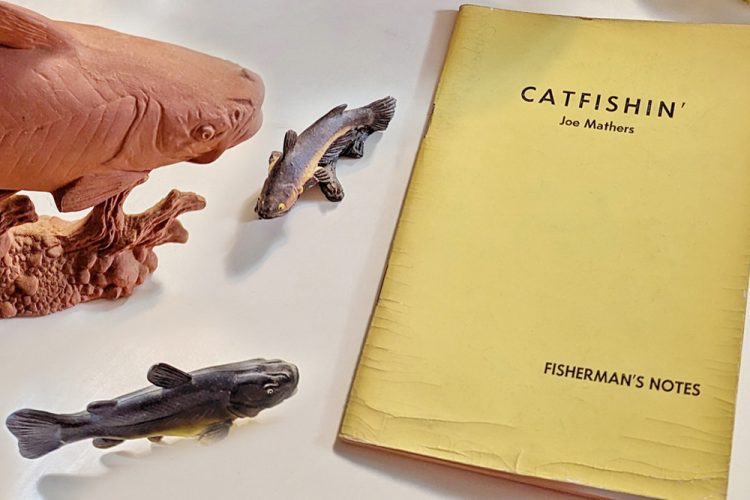

One great source of such information is a little-known booklet titled “Catfishin’.” Written in 1953, it’s just 33 pages long. But it’s full of great tips that are still just as applicable today as they were 70 years ago when the pocket-sized booklet was published.

The author, Joe Mathers, was an experienced amateur ichthyologist who had more than 25 years of catfishing experience under his belt. He was a zoologist on the staff at the State University of Iowa, and he had planned for the booklet to be the first in a series called “Fisherman’s Notes.”

Whether he ever completed other parts of the series, I’ve been unable to determine. Yet included in “Catfishin’” are tons of facts about catfish identification, fishing techniques, habitats, feeding habits and baits that were designed to encourage further interest in what Mathers called “a grand exciting sport, which, year-after-year, is becoming more and more popular.” Some of his tips, presented here as he wrote them, will prove to be enlightening to the beginner and amateur catfisherman as well as the experienced old-timer.

On Rising Rivers

“If the river reaches a very swift rate of flow, or floods, the fish will stop feeding and seek-out some protection from the rampaging waters. They will hug the bottom; take refuge in more quiet places as behind boulders, snags or sunken logs; retire in long bends in the rivers where the current is slowed; move into backwaters or ascend smaller, less-swift streams. As the larger streams back up into these smaller tributaries, all kinds of free-living water animals also crowd there for relief. So as the catfish enter these more protected spots, they move into a feeding paradise—a feeding ground containing crayfish, water bugs and beetles, minnows, chubs, shiners, suckers, crappie, perch, sunfish and many others. From this arises a good fishing tip. When the larger rivers and streams become high-to-flooding, fish the smaller feeder streams, especially near the inlets.”

On Baits

“Small frogs, night crawlers, large leeches, crayfish, living or dead minnows or other small fish or larger forms of these cut into chunk baits all are good baits in the spring. Best baits especially for the pole fisherman during summer are chicken blood, concocted blood baits, poultry livers, stink baits such as sour clams, sour minnows or concocted cheese baits. In the fall as natural foods become more scarce, large fish especially, often feed exclusively on small frogs, lively minnows, chubs, shiners and other small fish (soft and game). When available, crayfish, frogs, minnows, chubs, shiners, other small fish (living or dead, fresh or sour) and chunk baits of suckers, redhorse, quillback, shad and buffalo are commonly good anytime of the fishing season. Probably the best fish getter for the pole fisherman throughout the whole fishing season is chicken blood and, to a lesser extent, poultry livers.”

On Time of Day

“Anywhere one fishes, catfish bite better at night, and a combination of darkness and muddy, rising waters make them bite still better. Daytime fishing in rising, muddy waters proves very productive. The muddy waters cover the movements of the fish in shallow waters by excluding the sunlight. They sometimes feed on shoals so shallow the dorsal fin extends above the water.”

On Senses

“As a catfish is lying at rest in its lair or moving upstream, the flexible, rubber-like barbels are extended, contacting food substances and constantly picking up dissolved taste substances carried by the stream; the olfactory sacs are getting odors; the lateral lines are continually receiving sound vibrations, pressure changes or wave or current movements set up by various objects in the water (living or dead, moving or non-moving). When the catfish contacts food, gets a favorable odor or taste from upstream or perceives the presence of a nearby object, it quickly moves to it ready to have a meal.”

On Organic Matter in the Water

“During times when a stream is carrying a great amount of organic matter such as fallen leaves, seeds, fruits, algae and other plant materials, catfishing is apt to be poor. Either because the fish are gorging themselves with these materials, or as in the autumn the fallen leaves clog the stream and cover or screen you baits, prohibiting them from the fish. In the spring, catfish will often fill their stomachs with seeds such as those of the elm trees and refuse more appetizing flesh or concocted baits. If so, try a doughball bait made with ground or pulverized elm seeds.”

On Oxygen-Carbon Dioxide Relations

“When there is a lack of oxygen or/and a heavy concentration of carbon dioxide in the water, fish do not eat for they do not feel well. Oxygen is necessary for normal body processes and excessive carbon dioxide interferes with these processes. These conditions occur especially in shallow, quieter bodies of water during hot summer months. Hot weather reduces the solubility of oxygen. Cool waters hold more oxygen than warm waters, and in warm waters, decomposition of organic matter takes place more rapidly, thus reducing the oxygen supply and producing more carbon dioxide. The oxygen may be replenished by water agitation—rainfall splashing, wave action and turbulences due to obstructions. Fishing in smaller bodies of water, therefore, during hot months will be best after heavy winds causing wave action and heavy rainfall, and in deep holes around snags, roots of trees and other obstructions where the oxygen supply is kept near normal.”